The new 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans represent a turning point for children’s health. As an integrative pediatrician, I’ve waited years for federal nutrition policy to catch up with what we’ve known in integrative medicine all along: food is medicine, gut health is foundational, and ultra-processed foods are harming our kids. Here’s my analysis of what parents need to know.

A Historic Moment in Federal Nutrition Policy: What Every Parent Needs to Know

Over 54% of American children now have at least one chronic disease. (1) These aren’t just statistics – these are our children, our patients, our grandchildren, our future.

And here’s what should have been a wake-up call two decades ago: In 2005, a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine (2) made a prediction that should have stopped us all in our tracks. For the first time in modern history, researchers projected that our children would have shorter lifespans than us, their parents, due to diet and lifestyle-related diseases.

That alarm was largely ignored. But you and I – we didn’t ignore it. That study is part of why I have made it my mission to revolutionize the future of children’s health. Why I wrote my book, Healthy Kids, Happy Kids. And why I’ve dedicated my career to teaching families that Food IS Medicine – that what we feed our children shapes not just their weight, but their immune systems, their brains, their genes, and their futures.

So when the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans were released on January 7, 2026, I paid close attention. And I have to acknowledge that something remarkable happened. For the first time in federal nutrition history, the government officially recognized what I’ve been teaching families for over a decade: that a healthy, happy gut is the foundation for healthy, happy kids.

The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans represent what HHS Secretary Kennedy and USDA Secretary Rollins call “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in our nation’s history.” And while I don’t agree with everything in these guidelines, I have to acknowledge: there’s finally federal recognition that ultra-processed foods are harmful, that added sugars have no place in our children’s diets, and most exciting for me, that gut health matters.

Because here’s what we know to be true: what happens in the gut does not stay in the gut. With 70-80% of our immune cells residing in the gut, and approximately 95% of our serotonin produced there, the gut-immune connection, the gut-brain connection, and the gut-genes connection explain why nutrition matters far beyond calories. And finally, federal guidelines are beginning to acknowledge this fundamental truth.

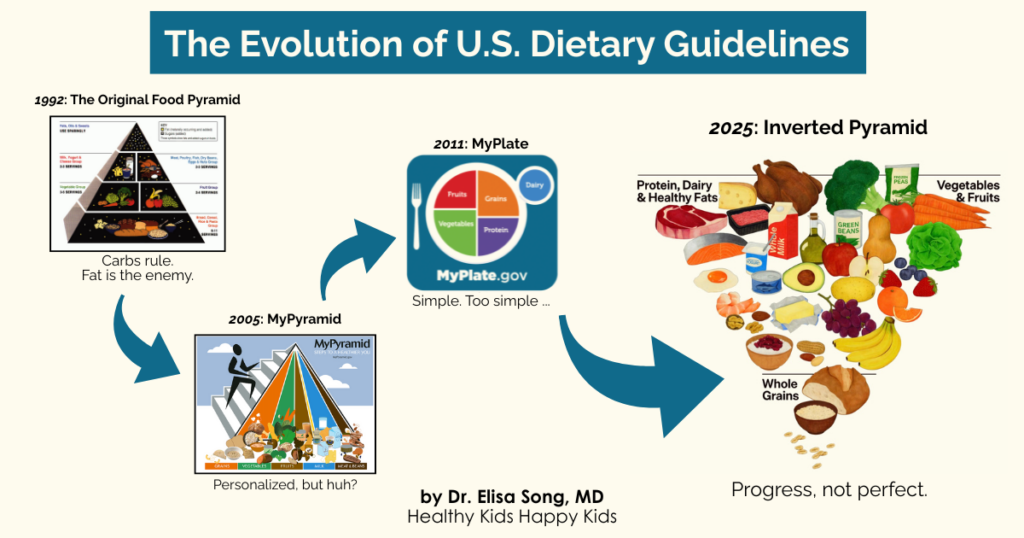

As an integrative pediatrician who has spent my career bridging the gap between conventional and functional medicine, I’ve watched federal nutrition guidance evolve over decades. I’ve seen the Food Pyramid, MyPyramid, and MyPlate come and go. And through it all, I’ve been in my clinic seeing what actually helps children thrive – not just survive.

This is my comprehensive analysis as an integrative pediatrician of what these new guidelines mean for our children. I’ll tell you what I applaud, where I have concerns, what’s still missing, and – most importantly – how to translate all of this into practical guidance for your family.

From the Food Pyramid to Today: How Federal Nutrition Guidance Has Evolved

To understand why these new guidelines matter, we need to understand where we’ve been. Federal nutrition guidance has evolved significantly over the past three decades, each iteration trying to solve different problems – with varying degrees of success.

1992: The Original Food Pyramid and the Low-Fat Era

The original Food Pyramid placed grains at the base, recommending 6-11 servings daily, with fats and oils at the tiny top to “use sparingly.” The goal? Combat rising rates of heart disease by reducing dietary fat.

What went wrong: This guidance inadvertently promoted excessive refined carbohydrate consumption. When Americans cut fat, they replaced it with sugar and processed carbs. The result? Obesity rates soared, and the foundations for cardiometabolic disease became established in childhood.

2005: MyPyramid and the First Steps Toward Personalization

MyPyramid introduced vertical colored bands instead of horizontal tiers, added a figure climbing stairs to emphasize physical activity, and introduced the concept of personalized nutrition. The visual was confusing, but the acknowledgment that one size doesn’t fit all was a step forward.

What was still missing: Any recognition of food quality beyond “whole grain vs. refined.” Processed foods and real foods were treated essentially the same if they hit the same macronutrient targets. And the gut microbiome was not even on the radar.

2011: MyPlate – Simple But Missing the Point

MyPlate simplified the visual to a plate divided into four sections – fruits, vegetables, grains, and protein – with a small dairy circle on the side. It was intuitive and memorable, which helped with public messaging.

But it still failed to distinguish food quality. A plate of processed chicken nuggets, canned fruit in syrup, white bread, and iceberg lettuce technically “checked the boxes” while providing minimal nutrition and actively harming the gut microbiome. And low-fat dairy was still the recommendation – ignoring emerging evidence about the benefits of full-fat dairy and the metabolic costs of low-fat, often sugar-laden alternatives.

2025: The Inverted Pyramid – A Philosophical Shift

Now we have something visually and philosophically different: an inverted pyramid with protein, dairy, and healthy fats sharing the top position alongside vegetables and fruits, while whole grains are minimized at the bottom.

This visual shift matters. It reflects a fundamental change in thinking – away from the carbohydrate-centric model that dominated for decades, toward a protein-first, real-food-focused approach. It’s not perfect (I’ll get to my concerns), but it represents genuine progress.

Most importantly for families: these guidelines finally acknowledge that ultra-processed foods and added sugars are problems to avoid, not just “sometimes foods” to moderate. And for the first time, federal guidance recognizes that the gut microbiome matters.

What Changed: The 7 Most Important Updates for Children’s Health

| Topic | 2020-2025 DGA | 2025-2030 DGA |

| Ultra-Processed Foods | Not addressed | First explicit call to “avoid” |

| Added Sugars | Limit to <10% calories | “No amount recommended” |

| Dairy | Low-fat/fat-free preferred | Full-fat recommended (3 servings) |

| Protein | 0.8g/kg body weight (RDA minimum) | 1.2-1.6g/kg body weight |

| Gut Microbiome | Not mentioned | First federal recognition; fermented foods named |

| Breastfeeding | 6 months exclusive, 1+ year total | 6 months exclusive, 2+ years recommended |

| Early Allergens | Limited guidance | Early introduction (4-6 months) encouraged |

Ultra-Processed Foods: The First Federal Call to “Avoid”

For the first time, federal dietary guidelines explicitly call out ultra-processed foods as a category to avoid. The language is clear: “Avoid highly processed, packaged, prepared, ready-to-eat, or other foods that are salty or sweet, such as chips, cookies, and candy that have added sugars and sodium.”

The guidelines also call for limiting “foods and beverages that include artificial flavors, petroleum-based dyes, artificial preservatives, and low-calorie non-nutritive sweeteners.”

Why does this matter so much? According to the CDC’s most recent analysis using NHANES data from 2021-2023 (3), American youth ages 1-18 consume almost two thirds of their daily calories from ultra-processed foods, with children ages 6-11 having the highest intake. This isn’t just about empty calories. These ultra-processed foods also wreak havoc on kids’ developing gut microbiome, and right along with it, their gut-immune and gut-brain development.

Research published in Nutrients in 2023 (4) confirms that ultra-processed foods don’t just fail to nourish beneficial gut bacteria, they actively harm them. Food additives like emulsifiers (including carageenan, xanthan gum, carboxymethylcellulose, or CMC) can disrupt the gut lining. Artificial sweeteners (like sucralose, acesulfame potassium (Ace-K), and saccharin) can alter the gut microbiome in ways that paradoxically worsen metabolic health. And the lack of fiber means these foods provide no benefit to the beneficial bacteria that support your child’s immune system, brain function, and overall resilience.

In my practice, moving from ultra-processed foods to real food is often the single most impactful change families can make.

Become a Gut Hero Food Label Detective! Teaching your kids to be food label detectives is one of the most important life skills you can give them – that’s exactly why I devote a whole section on this in my Healthy Kids, Happy Kids book! If you can’t pronounce the ingredients or the list is longer than a paragraph, it’s probably a Microbiome Mischief Maker. Focus on foods with short ingredient lists of recognizable whole foods. A pizza made with pizza dough made from flour, water, yeast, and salt (that’s it) and topped with marinara sauce with no added sugar, mozzarella cheese, and fresh vegetables with no emulsifiers, preservatives, or artificial flavors – that’s a whole foods meal. A frozen pizza with 40 ingredients – that’s not.

Added Sugars: “No Amount Recommended” – A Historic Stance

This is the strongest position any federal guideline has ever taken on added sugars. The language is unprecedented: “While no amount of added sugars or non-nutritive sweeteners is recommended or considered part of a healthy or nutritious diet, one meal should contain no more than 10 grams of added sugars.”

Let that sink in: “No amount is recommended.” This is a complete reversal from previous guidelines that simply advised limiting sugar to less than 10% of daily calories. For children under 4, the new guidelines recommend zero added sugars.

From a gut perspective, this makes perfect sense. Sugar is a major Microbiome Mischief Maker that I discuss in my book, which feeds potentially pathogenic microbes in the gut and can crowd out the beneficial bacteria we want to support. And we now understand the gut-brain axis well enough to know that the bacterial balance in the gut directly influences mood, behavior, focus, and emotional regulation through the vagus nerve and neurotransmitter production.

And one of the most important recommendations that I want to shout from the rooftops is to limit intake of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB). SSBs have become a daily habit for many kids and adults. For children 2-18 years of age, the American Heart Association recommends no more than 25 grams (~6 teaspoons) of added sugar daily. (6) A Starbucks Grande Mocha Cookie Crumble Frappuccino has 55 grams (~13 teaspoons) of added sugar. And if you think you’re going for a healthier option with a Boba Guys Strawberry Jasmine Fresca with 44 grams (~11 teaspoons) of added sugar, or a Starbucks Grande Oatmilk Matcha Latte with 28 grams of added sugar (~7 teaspoons) – think again.

The UK Sugar Rationing Study: Proof That Early Sugar Exposure Has Lifelong Consequences

If you need evidence that early life sugar exposure matters for long-term future health through adulthood, look no further than a remarkable natural experiment from World War II. (6) During the UK sugar rationing period (1942-1953), children consumed dramatically less sugar than subsequent generations, in quantities similar to our current American Heart Association recommendations. Researchers who followed these children for 50-60 years found something remarkable: those who grew up during rationing had a 35% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes and a 20% lower risk of hypertension compared to those born just after rationing ended.

The effects persisted for half a century. This is epigenetics in action – early nutritional exposures literally programming metabolic health for a lifetime. It’s why the First 1,000 Days matter so much, and why the “zero added sugars under 4” recommendation could be transformative, as long as it is enforceable.

The Problem: Guidelines Without Enforcement

This historic “no added sugar” recommendation is a powerful step, but guidelines are only as good as their enforcement. There’s a major labeling loophole in FDA rules that allows the food industry to use processed fruit purées (stripped of fiber, essentially leaving just the sugar behind) to sweeten products while legally claiming “No Added Sweeteners.” Your baby’s microbiome can’t tell the difference between table sugar and highly processed apple puree. I’ll explain exactly how to protect your family in my “Where I Have Concerns” section, because this is where we need real policy change, not just individual action.

Infant and Toddler Nutrition: Why the First 1,000 Days Matter Most

The new guidelines place significant emphasis on early life nutrition, which aligns perfectly with what we know about the First 1,000 Days – the period from conception through approximately age 2.5 that represents a critical window for microbiome development and an infant’s future immune, brain, and metabolic health.

Key recommendations include exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months when possible, continuing breastfeeding for 2 years or longer (up from previous guidance), Vitamin D supplementation for infants, and early introduction of common allergens between 4-6 months of age. The science is clear that early, diverse exposure helps train the immune system and may actually prevent food allergies rather than cause them. (7)

A Note on Infant Formula

Breastmilk is best for the microbiome – but breastfeeding is not always successful, or possible, and no mother should be made to feel guilty for the choices she makes for herself and her baby. Some mamas struggle despite their best efforts. Others face medical conditions or medication requirements that prevent breastfeeding. Formula feeding is not a failure. Fed is best.

When formula is your family’s path, you deserve safe, high-quality options. Unfortunately, FDA regulation of infant formula has not been as rigorous as standards in the European Union. The recent ByHeart botulism outbreak (8) – which sickened 51 infants across 19 states, with Clostridium botulinum confirmed in formula samples – exposed dangerous gaps in infant formula oversight. Retailers continued selling recalled formula for weeks. This is unacceptable for our most vulnerable population.

In addition, FDA requirements for infant formula have not kept up with the latest research on optimal nutrition for infants. Their guidelines must ensure that manufacturers use the highest quality, evidence-based ingredients that optimize infant brain, gut microbiome, and immune development. This should include organic ingredients, 100% lactose as the primary sugar (no corn syrup or maltodextrin), using folate instead of folic acid and methylcobalamin instead of cyanocobalamin, Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs) like 2′-FL and LNnT that support Bifidobacteria colonization, DHA for brain development, and no emulsifiers like carrageenan that can disrupt the developing microbiome. Outdated FDA regulations must keep up with the latest science in optimizing infant nutrition.

Early Allergen Introduction: Evidence-Based Progress

For decades, conventional advice was to delay allergenic foods until at least age 1. We now know this was not just wrong, but may have contributed to the dramatic rise in food allergies over the past 30 years. This guidance reflects one of the most important, evidence-based recommendations in the entire document, supported by landmark research including the LEAP trial, which showed early peanut introduction reduced peanut allergy by 81% in high-risk infants. (9) Follow-up studies confirmed this protection persists through at least age 12. (10, 11)

The guidelines appropriately distinguish risk levels:

- High-risk infants (severe eczema and/or egg allergy): Introduce peanut-containing foods at 4-6 months after consulting with your healthcare provider.

- Infants with mild to moderate eczema: Introduce peanut-containing foods around 6 months.

- All infants: Introduce other potentially allergenic foods (eggs, shellfish, wheat, nut butters) at about 6 months.

This shift from “avoid allergens” to “introduce early” represents exactly what evidence-based medicine should look like: updating recommendations when better science emerges, even when it means reversing decades of previous advice.

Gut Microbiome Recognition: Federal Validation of “All Health Starts in the Gut”

For the first time, federal dietary guidelines explicitly acknowledge the gut microbiome as a factor in health.

This is especially important for children’s health, and exactly why I wrote my book Healthy Kids, Happy Kids: An Integrative Pediatrician’s Guide to Whole Child Resilience, which teaches why and how your child’s microbiome lays the foundation for lifelong wellness.

The guidelines specifically name fermented foods, including kimchi, sauerkraut, kefir, and miso, as beneficial for gut health. A landmark Stanford study (12) found that eating fermented foods for just 10 weeks increased overall microbial diversity and decreased markers of inflammation in the body. The researchers noted that greater microbial diversity is generally associated with better health outcomes.

This federal recognition validates one of the most important principles in functional medicine: “All diseases begin in the gut.” This is not a new concept – in fact, Hippocrates, the founder of modern medicine, is credited with saying this over 2000 years ago. It’s about time our dietary guidelines caught up!

The Evidence: Early Gut Disruption Has Lifelong Consequences

Two landmark studies demonstrate just how critical early microbiome health is for lifelong outcomes. A military health system study (13) of nearly 800,000 infants found that babies who received antibiotics or antacid medications in the first 6 months of life had a significantly increased risk of virtually every allergic disease by age 2 – including eczema, asthma, anaphylactic food allergies, allergic rhinitis (hayfever), and hives. These medications disrupt the developing microbiome during a critical window when the immune system is being trained.

A Finnish study (14) took this even further, examining mental health outcomes. The research found that antibiotic exposure in infancy increased the risk of mental health disorders – including depression, anxiety, and behavioral disorders – in later childhood and adolescence by up to 50%. The gut-brain axis is real, and disrupting it early has consequences that extend far beyond digestive health.

“Your child’s microbiome lays the foundation for lifelong wellness.”

Protein Recommendations: Higher Targets, But Which Proteins Matter?

The new guidelines recommend a protein target of 1.2-1.6g per kilogram of body weight, which is significantly higher than the long-standing RDA minimum of 0.8g/kg. While this may be beneficial for adults who are physically active or trying to lose weight, this shift deserves age-specific analysis, because the implications vary dramatically depending on your child’s stage of life

For infants and toddlers, “more protein” is not necessarily better. The European Childhood Obesity Project (CHOP), one of the largest randomized controlled trials on infant nutrition, found that infants fed higher-protein formula were 2.43 times more likely to be obese at age 6 compared to those fed lower-protein formula. (15) The 11-year follow-up confirmed these effects persisted through pre-adolescence. (16) High protein intake in infancy increases branched-chain amino acids, which stimulate insulin and IGF-1 secretion, activating pathways that promote fat cell creation. (17) This is early metabolic programming with decades-long consequences. A blanket “1.2-1.6g/kg” message risks being misinterpreted as “more is better” for our youngest children, when the science suggests caution.

The guidelines miss an opportunity to emphasize the diversity of plant proteins for gut health. While quality animal proteins can certainly be part of a healthy diet, the heavy emphasis on animal protein sources overlooks a key functional medicine principle: legumes, nuts, and seeds provide prebiotic fibers alongside protein, which feed beneficial gut bacteria while meeting protein needs. When families focus on “hitting the protein number,” they often crowd out these fiber-rich foods. More chicken nuggets, fewer beans. More cheese sticks, fewer vegetables. If your child meets the protein target by displacing prebiotic fibers, you can worsen gut health while technically “meeting macros.”

Protein quality matters more than protein quantity. An egg provides choline for brain development. Legumes provide prebiotic fiber. Fatty fish provides omega-3s. Yogurt and kefir provide probiotics. Processed protein bars or protein shakes, often laden with emulsifiers and artificial flavors and sweeteners, are not the same as whole-food protein sources – and I see too many teens skipping meals and loading up on protein bars and protein shakes simply to meet their self-imposed protein requirements. Protein quality matters.

Full-Fat Dairy: The End of the Low-Fat Era

Perhaps one of the most significant reversals is the shift from low-fat to full-fat dairy recommendations. The guidelines now recommend 3 servings of full-fat dairy daily, acknowledging what research has shown for years: full-fat dairy is not the enemy it was once portrayed to be.

The Dairy Caveat: One Size Does Not Fit All

Here’s what the guidelines miss: dairy is one of the top food allergens and sensitivities in children. While I agree that full-fat is better than low-fat when dairy is tolerated, the blanket recommendation of 3 servings daily doesn’t account for the growing number of children with dairy allergies, intolerances, and sensitivities.

For many children, dairy is inflammatory. The A1 β-casein protein can disrupt the gut microbiome (18) in sensitive individuals, contributing to the very health issues we’re trying to prevent. Signs that dairy may be problematic for your child include chronic congestion, eczema, digestive issues, recurrent ear infections, and behavioral changes.

On the other hand, the A2 β-casein is associated with improved gut health outcomes, including increased abundance of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium spp. and reduced levels of inflammatory markers. The type of dairy matters.

If your child tolerates dairy well, full-fat organic dairy from grass-fed sources is a nutrient-dense choice. But if dairy is causing problems, you can first try switching to A2 dairy products – look for milk, yogurt, and cheese specifically labeled “A2” or from heritage breeds like Jersey, Guernsey, or goats and sheep (which naturally produce A2 casein). And if your child doesn’t tolerate dairy at all, there are plenty of ways to get those fat-soluble vitamins and healthy fats elsewhere – from egg yolks, fatty fish, avocados, nuts, and seeds. Don’t force 3 servings of dairy if your child’s body is telling you it’s not working for them.

The Saturated Fat Paradox: Where Science and Policy Collide

Here’s where things get complicated. While the guidelines recommend full-fat dairy, they still maintain the recommendation to limit saturated fat to less than 10% of daily calories. These two positions create inherent tension that families may find confusing to navigate.

The nuance that’s missing: not all saturated fats are created equal, and the source matters enormously. Saturated fat from processed foods affects the body differently than saturated fat from whole food sources like full-fat yogurt or eggs. Context matters, and blanket restrictions can obscure important distinctions.

Where We Go From Here: Policy Gaps, Industry Loopholes, and the Changes Our Children Need

As a pediatrician, despite the wins I just mentioned, I’m struck by how little of the Scientific Foundation’s evidence base specifically addresses children and teens. The document dedicates just 3 pages to all pediatric life stages combined – infancy through adolescence – while devoting far more space to adult outcomes like cardiovascular disease and weight loss.

Children are not little adults. Infant protein needs differ from toddler needs, which differ from adolescent needs. A one-size-fits-all approach to macronutrients does not reflect the nuanced, age-specific evidence that should guide pediatric nutrition policy. Future guidelines should prioritize pediatric-specific research and include more pediatric experts in the review process.

In addition, progress without enforcement is just words on paper. About 50% of independent scientific recommendations were not reflected in the final guidelines, and half the final panel had industry ties. The sugar labeling loophole lets manufacturers deceive parents. Individual family choices matter, but systemic change requires policy: microbiome testing as standard newborn screening, infant formula safety enforcement, sugar labeling reform, front-of-package warning labels, and state-level bans on harmful additives. Real change requires us to demand it.

As an integrative pediatrician, I’ve spent decades helping individual families optimize their children’s health. But here’s what I’ve learned: individual choices, no matter how good, cannot overcome systemic failures. The families with the most resources can navigate around food industry deception. The families without those resources cannot. That’s not personal responsibility – that’s policy failure.

We have the power to rewrite our children’s – and our grandchildren’s – epigenetic futures. But it requires more than individual action. It requires policy change.

The Process Problem: Transparency and Industry Influence

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) – a panel of 20 independent scientific experts – submitted its comprehensive report after years of evidence review. According to available reporting, more than 50% of the DGAC’s recommendations were not reflected in the final guidelines.(19) This raises legitimate questions about the relationship between independent scientific review and final policy decisions.

Reports indicate that 5 of the 10 members on the final panel that shaped these guidelines had ties to the beef, pork, dairy, or infant formula industries.(20) This doesn’t automatically invalidate their input, but it’s information families deserve to know when evaluating the guidelines. Transparency matters for public trust.

What’s Missing: Plant Protein Diversity for Gut Health

The guidelines’ heavy emphasis on animal protein sources, while valid from a protein quality standpoint, misses an opportunity to emphasize the gut health benefits of plant protein diversity. Legumes, for example, are protein sources that also provide prebiotic fiber – feeding beneficial gut bacteria while meeting protein needs. A more balanced approach would acknowledge that HOW we get our protein matters for the microbiome, not just how much.

The Enforcement Problem: Guidelines Without Teeth

The “no added sugar” recommendation is historic – but without addressing labeling loopholes and food industry accountability, it’s largely toothless. The food industry has found a way around it, and the FDA is allowing it.

The Sugar Labeling Loophole: How Industry Deceives Parents

The FDA does not count fruit purées as “added sugars” on nutrition labels. Technically, they’re classified as “fruit.” This means food manufacturers can use fruit purées that have been pulverized to eliminate all fiber, and essentially leave concentrated sugar to sweeten baby foods and toddler snacks – to make products taste as sweet as if they’d added table sugar, and legally claim “No Added Sweeteners” on the front of the package – while the product still delivers a concentrated sugar hit to your baby.

Your baby’s developing palate and gut microbiome can’t tell the difference between white sugar and concentrated apple juice. Sugar is sugar when it comes to the metabolic and microbiome effects. Yet one triggers the “added sugar” label, and one doesn’t.

The Sugar Labeling Loophole: When a food label shows 0g “Added Sugars” but the ingredient list contains fruit purée, your child is still getting concentrated sugars – they’re just not being labeled as such. This is why it’s so important to learn how to be a savvy Gut Hero Food Label Detective.

Case Study: YoBaby Yogurt – Industry Deception in Action

Stonyfield YoBaby yogurt is marketed with all the right buzzwords: “Organic,” “#1 Pediatrician Recommended,” and “No Added Sweeteners.” Parents trust this product. Look at the nutrition label: Added Sugars shows 0g. But check the ingredient list: strawberry purée and banana purée. Now look at Total Sugars: 6 grams per serving. That’s 6 grams of concentrated fruit sugars hitting your baby’s system – training their palate to expect sweetness, feeding sugar-loving gut bacteria, and potentially setting up harmful metabolic patterns later in life. But because it comes from fruit purée rather than cane sugar, it doesn’t count as “added” sugar under FDA rules.

This isn’t about vilifying one company. This loophole is industry-wide. It’s about understanding that “No Added Sweeteners” is often marketing designed to help companies sell products, not science designed to help parents make informed choices.

The WHO Has Already Addressed This

The World Health Organization has taken a much stronger position than the US federal guidelines. WHO Europe (21) found that approximately one-third of commercial baby foods contain added sugars and that many products – Including savory meals – derive excessive calories from sugar, often due to added fruit purées. Their recommendations include prohibiting added sugars (including concentrated fruit juice), limiting the use of fruit purées in certain product categories, and requiring clear labeling of total sugar content. They’ve explicitly recommended that sweetened products NOT be marketed for children under 3. Our FDA needs to catch up.

Parents (and kids) deserve transparent food labeling aligned with science-based policy recommendations – not industry loopholes that hide the truth.”

Nutrition Equity IS Health Equity

Guidelines are only as good as families’ ability to implement them. For the approximately 18.8 million Americans living in food deserts – areas with limited access to affordable, nutritious food – these recommendations can feel impossibly out of reach. And food swamps – areas with adequate grocery access but overwhelming fast food and convenience stores – increase obesity-related cancer mortality by 77%.

For nearly 29.4 million children who participate in the National School Lunch Program (22) daily, school meals may be the most reliable source of nutrition. When we improve school food quality – removing harmful additives, increasing whole foods, supporting farm-to-school programs – we address equity at scale. This is exactly why state legislation matters: it creates systemic change that protects all children, not just those whose families can afford to opt out.

The Policy Changes Our Children Need

Upstream Solutions: Protecting Children Before Problems Begin

The First 1,000 Days from conception through age 2.5 represent a critical window for microbiome-epigenetic programming. If we’re serious about early intervention, here’s what policy should look like:

Microbiome testing as standard newborn screening: We screen newborns for dozens of rare metabolic conditions, yet the 2025 My Baby Biome study (23) – the largest investigation of infant microbiomes in the US to date – found that 3 in 4 babies have deficient levels of their most important keystone bacteria, Bifidobacteria, and 1 in 4 babies have no Bifidobacteria at all! Babies without adequate Bifidobacteria are 3 times more likely to develop eczema, asthma, or allergies by age 2. Early identification allows early intervention.

Microbiome education as standard care: Every expecting parent should understand how birth mode, feeding choices, and antibiotic exposure affect their baby’s microbiome development. The 2025 Infant Restore study (24) demonstrated that when parents of babies born by cesarean section received microbiome education, personalized testing, and targeted probiotic guidance, their babies had 83% lower odds of developing eczema. When at least 1 in 5 babies has eczema, this should be standard curriculum in every OBGYN, family medicine, and pediatrics residency.

Lactation support that matches the guidelines: The guidelines recommend breastfeeding for 2+ years, but our workplace policies don’t support it. Meaningful lactation support – including paid parental leave, protected pumping time, and accessible lactation consultation – must be policy priorities.

Infant Formula Safety: The ByHeart Wake-Up Call

When breastfeeding isn’t possible – and no mother should feel guilty when it isn’t – families deserve safe, high-quality formula options. The November 2025 ByHeart botulism outbreak exposed dangerous gaps in infant formula oversight. Fifty-one infants were hospitalized across 19 states. Clostridium botulinum was confirmed in formula samples. Retailers continued selling recalled formula for weeks, with FDA warning letters going to Walmart, Target, Kroger, and Albertsons.

We need stronger FDA oversight of infant formula manufacturing and testing, mandatory heavy metal testing for all infant formula and baby foods, clear infant formula standards that prioritize optimal ingredients as discussed above – not just minimum safety thresholds – and retail systems that can execute recalls within hours, not weeks.

Downstream Solutions: Removing Microbiome Mischief Makers at Scale

Sugar policy reform: Close the FDA labeling loophole so fruit purées count as added sugars. Implement front-of-package “High in Sugar” warning labels like Mexico and Chile. Ban marketing of sweetened foods to infants and toddlers. Align federal nutrition programs with zero-added-sugar standards for young children.

Ultra-processed food policy: States are leading the way here (25), and all states should follow suit. California’s AB 1264 creates the nation’s first UPF phase-out in public school meals by July 2035. Texas SB 314 bans harmful additives, including brominated vegetable oil, BHA, Red 3, and Yellow 5/6, in school meals. West Virginia’s HB 2354 bans synthetic dyes. Arizona’s HB 2164 bans 11 harmful additives. These state-level actions create pressure for federal change.

Antibiotic stewardship: Just one dose of antibiotics increases the risk of infections, asthma, allergies, anxiety, type 1 diabetes, and childhood obesity. (26) Antibiotic use in infancy can increase the risk of later allergic disease and mental health disease by up to 50%. (27) But we can’t talk about antibiotic stewardship without addressing a major source: our food supply. The beef, pork, poultry, and dairy industries use antibiotics extensively (28) – for growth promotion and disease prevention in crowded conditions, not just treatment of sick animals. Antibiotic residues and antibiotic-resistant bacteria have been found in dairy products and meat. Given the industry ties on the DGA final panel, the absence of guidance on antibiotic exposure through food is a glaring omission. We need systematic change in agricultural antibiotic practices, not just prescribing practices.

Environmental protections: Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) should really be called microbiome-disrupting chemicals (MBCs) to explain why they have such far-reaching negative health effects on children beyond hormones. (29) Glyphosate, BPA, phthalates, heavy metals, and PFAS all affect gut microbiome composition and function, which can have far-reaching effects on children’s brain, immune, metabolic, and hormone functioning now and later in life.

Yet environmental protections are being dismantled. The current administration has proposed sweeping rollbacks of many environmental policies – weakening air quality standards, reducing EPA enforcement capacity, and even attempting to revoke the 2009 endangerment finding that allows regulation of greenhouse gases. Children are uniquely vulnerable: pound for pound, they breathe more air, taking in more relative amounts of pollutants, and their developing organs and microbiomes are more easily harmed by environmental toxins. We need stronger environmental protections that prioritize children’s developing systems and safer consumer product standards, not weaker ones.

The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines represent progress. But progress without enforcement is just words on paper. Real change – the kind that protects all children, not just those whose families can navigate around industry deception – requires policy. And policy requires us to demand it.

What Families Can Do Now: Building on the Guidelines

While we advocate for policy change, families don’t have to wait. The new guidelines provide a foundation—here’s how to build on it with the integrative approaches I’ve developed over two decades of practice.

Be a Gut Hero™ for Life

The federal guidelines are a starting point. In my book Healthy Kids, Happy Kids, I detail the frameworks that take families further: aiming for 30 plants per week with the Whole Gut Rainbow approach, making the 5 Things for Microbiome Magic™ (Nourish, Breathe, Move, Drink, Sleep) a way of life, choosing Microbiome Champions over Mischief Makers, and teaching kids to be Gut Hero Food Label Detectives.

Gut health is about more than just food – it’s whole child resilience.

Join Me in My Mission to Revolutionize the Future of Children’s Health

These guidelines represent a turning point – but turning points only matter if we keep moving forward.

For over a decade, I’ve been teaching families that a healthy, happy gut creates healthy, happy kids. I’ve watched children transform when we address root causes rather than just symptoms. I’ve seen “persistent” conditions resolve when we give the body (and the gut microbiome) what it needs to heal.

This is what I know to be true: we have the power to rewrite our children’s health trajectories. Not someday. Now.

My mission is to revolutionize the future of children’s health by empowering families with the knowledge and tools to help their children thrive from the inside out. The science is clear. The guidelines are finally catching up. Now it’s up to us – parents, practitioners, policymakers, and communities – to turn knowledge into action.

I’m so grateful to be on this journey with you. Together, our children will thrive!

xo Elisa Song, MD

References:

- Bethell, C. D., Kogan, M. D., Strickland, B. B., Schor, E. L., Robertson, J., & Newacheck, P. W. (2011). A national and state profile of leading health problems and health care quality for US children: Key insurance disparities and across-state variations. Academic Pediatrics, 11(3), S22–S33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2010.08.011

- Olshansky, S. J., Passaro, D. J., Hershow, R. C., Layden, J., Carnes, B. A., Brody, J., Hayflick, L., Butler, R. N., Allison, D. B., & Ludwig, D. S. (2005). A potential decline in life expectancy in the United States in the 21st century. New England Journal of Medicine, 352(11), 1138–1145. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr043743

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2025). Ultra-processed food consumption in youth and adults: United States, 2021–2023 (NCHS Data Brief No. 536). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Brichacek, A. L., Beez, M., & De Mello, V. D. (2024). Ultra-processed foods: A narrative review of the impact on the human gut microbiome. Nutrients, 16(11), 1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16111738

- Vos, M. B., Kaar, J. L., Welsh, J. A., Van Horn, L. V., Feig, D. I., Anderson, C. A. M., Patel, M. J., Cruz Munos, J., Krebs, N. F., Xanthakos, S. A., Johnson, R. K., & American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; and Council on Hypertension (2017). Added Sugars and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Children: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 135(19), e1017–e1034. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000439

- Gracner, T., Boone, C., & Gertler, P. J. (2024). Exposure to sugar rationing in the first 1000 days of life protected against chronic disease. Science, 386(6719), adn5421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn5421

- Zhang, H., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., & Zhang, L. (2022). The complex link between the gut microbiome and the immune system in infants. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 12, 924119. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2022.924119

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, November–December). Outbreak investigation of infant botulism: Infant formula. https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness

- Du Toit, G., Roberts, G., Sayre, P. H., Bahnson, H. T., Radulovic, S., Santos, A. F., Brough, H. A., Phippard, D., Basting, M., Feeney, M., Turcanu, V., Sever, M. L., Gomez Lorenzo, M., Plaut, M., & Lack, G. (2015). Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(9), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1414850

- Du Toit, G., Sayre, P. H., Roberts, G., Sever, M. L., Lawson, K., Bahnson, H. T., Brough, H. A., Santos, A. F., Harris, K. M., Radulovic, S., Plaut, M., & Lack, G. (2016). Effect of avoidance on peanut allergy after early peanut consumption. New England Journal of Medicine, 374(15), 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1514209

- Du Toit, G., Huffaker, M. F., Radulovic, S., Gong, H., Roberts, G., Basting, M., Keat, K., Tsakok, T., Lack, G., & Plaut, M. (2024). Peanut allergy through 12 years of age: Follow-up from the LEAP trial. NEJM Evidence, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2300311

- Wastyk, H. C., Fragiadakis, G. K., Perelman, D., Dahan, D., Merrill, B. D., Yu, F. B., Topf, M., Gonzalez, C. G., Van Treuren, W., Han, S., Robinson, J. L., Elber, J. E., Sonnenburg, E. D., Gardner, C. D., & Sonnenburg, J. L. (2021). Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell, 184(16), 4137–4153.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.019

- Mitre, E., Susi, A., Kropp, L. E., Schwartz, D. J., Gorman, G. H., & Nylund, C. M. (2018). Association between use of acid-suppressive medications and antibiotics during infancy and allergic diseases in early childhood. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(6), e180315. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315

- Slykerman, R. F., Thompson, J., Waldie, K. E., Murphy, R., Wall, C., & Mitchell, E. A. (2017). Early childhood antibiotic exposure and subsequent mental health outcomes: A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(12), 1375–1385. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12781

- Weber, M., Grote, V., Closa-Monasterolo, R., Escribano, J., Langhendries, J. P., Dain, E., Giovannini, M., Verduci, E., Gruszfeld, D., Socha, P., & Koletzko, B. (2014). Lower protein content in infant formula reduces BMI and obesity risk at school age: Follow-up of a randomized trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 99(5), 1041–1051. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.064071

- Totzauer, M., Grote, V., Escribano, J., Closa-Monasterolo, R., Gruszfeld, D., Socha, P., Langhendries, J. P., Goyens, P., Verduci, E., Riva, E., & Koletzko, B. (2022). Different protein intake in the first year and its effects on adiposity rebound and obesity throughout childhood: 11 years follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatric Obesity, 17(12), e12961. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12961

- Koletzko, B., Broekaert, I., Demmelmair, H., Franke, J., Hannibal, I., Oberle, D., Schiess, S., Baumann, B. T., & Verwied-Jorky, S. (2005). Protein intake in the first year of life: A risk factor for later obesity? Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 569, 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3535-7_12

- González-Rodríguez, N., Vázquez-Liz, N., Rodríguez-Sampedro, A., Regal, P., Fente, C., & Lamas, A. (2025). The impact of A1- and A2 β-casein on health outcomes: A comprehensive review of evidence from human studies. Applied Sciences, 15(13), 7278. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15137278

- Center for Science in the Public Interest. (2026, January 7). New dietary guidelines undercut science and sow confusion [Press release]. https://www.cspinet.org/news/new-dietary-guidelines-undercut-science

- Todd, S. (2026, January 7). Panel behind new dietary guidelines had financial ties to beef, dairy industries. STAT News. https://www.statnews.com/2026/01/07/dietary-guidelines-industry-ties

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. (2019). Commercial foods for infants and young children in the WHO European Region. WHO. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289054157

- Food Research & Action Center. (2025). The reach of school breakfast and lunch. FRAC. https://frac.org/research/resource-library

- Jarman, J. B., Cockerham, L. R., Engstrand, L., & Franzen, O. (2025). Bifidobacterium deficit in United States infants drives prevalent gut dysbiosis. Communications Biology, 8, 412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-07825-2

- Nieto, P. A., Soto, J. A., & Kalergis, A. M. (2025). Improving immune-related health outcomes post-cesarean birth with a gut microbiome-based program: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 36(9), e14245. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.14245

- California State Legislature. (2025). AB 1264: Public school meals: Ultraprocessed foods; Texas State Legislature. (2025). SB 314: School nutrition standards; West Virginia State Legislature. (2025). HB 2354: Artificial dyes in school meals; Arizona State Legislature. (2025). HB 2164: School food additives.

- Aversa, Z., Atkinson, E. J., Schafer, M. J., Theiler, R. N., Rocca, W. A., Blaser, M. J., & LeBrasseur, N. K. (2021). Association of infant antibiotic exposure with childhood health outcomes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 96(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.019

- Lavebratt, C., Yang, L. L., Giacobini, M., Forsell, Y., Schalling, M., Partonen, T., & Gissler, M. (2019). Early exposure to antibiotic drugs and risk for psychiatric disorders: A population-based study. Translational Psychiatry, 9, 317. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0653-9

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (2024). Use of antibiotics in animal agriculture: Implications for pediatrics. Pediatrics, 154(4), e2024068591. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2024-068591

- Aguilera, M., Gálvez-Ontiveros, Y., & Rivas, A. (2020). Endobolome, a new concept for determining the influence of microbiota disrupting chemicals (MDC) in relation to specific endocrine pathogenesis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11, 578007. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.578007

Leave a Reply